Anthem of the Sun

Anthem of the Sun could be seen as the best expression of the Grateful Dead and how they would relate to the recording business and recorded music. The band never claimed to be oriented towards making music in the studio, and their efforts were initially geared towards trying to recreate the live sound in the studio, an endeavor that would prove impossible.

Anthem could be described as the first live studio album. The band explained to Warner Brothers that it was a studio album, while it was really an assembly of live tapes and studio work mixed together. The band used the studio to splice together an incredible number of live recordings and some studio takes, put together to form a suite that best simulated what they were doing in front of an audience. This idea came about after the band struggled to record in the studio. That, coupled with the extensive live recordings the band had, met with their desire to really learn how the studio worked, was the basic inspiration that drove Anthem. It was a strange response to the pressure Warner Brothers was putting on them to report progress. Once the idea was born to mix together live recordings as a collage, the direction was set, and the Dead told Warner it was not a live album. In a sense it was typical of the antics that characterized the Dead as independent pranksters, but also reflects their creativity—and the album itself was a formidable undertaking in the studio.

Anthem began in planning as a studio album proper at the end of 1967, where the band would find material and develop it for documenting in a studio, as would be the expectation. They accomplished some recording at RCA Studio A and American Studios in Los Angeles while the band lived together briefly in the Hollywood Hills, with Dave Hassinger still the producer. More work happened in New York at Century Sound and Olmstead Studios, and it was here that relations with Hassinger famously imploded when Bob Weir requested the ambient sound of ‘thick air,’ and it seems that from this episode the concept for Anthem was made solid, perhaps primarily in response to the floundering of the initial attempts to record.

The Dead’s contract with Warner Brothers obligated them to deliver three albums. Contracts like these, it can be argued, create pressure for artists, and they will either rise to the challenge and find a burst of creativity that brings forth quality music that is both commercially viable and hits home with listeners, or they are potentially just perfunctory by-products of contractual obligation. It is certainly a situation that so many artists can find themselves. The Dead were not without material to record, and by this time the members were stretching out to write original compositions. Anthem, in contrast to Grateful Dead, has only one cover arrangement.

By this time, the Dead had become a fixture in the San Francisco music scene, and they were becoming more than just the house band at Kesey’s acid tests. They were beginning to tour in the Pacific Northwest and in the East Coast. As an act, they were honing their sound and material, and extended exploratory jams were becoming the main thrust of their performances.

Anthem features the addition of Tom Constanten on piano and prepared piano. As the Dead’s material began to include more original compositions beyond the basic blues structure, and their music took on more of its improvisational forms, Pigpen began to struggle with the added complexity of the music, so Constanten was brought in to fill the vacuum, in part. This also marks the first album with second drummer Mickey Hart, who joined the band in 1967, when he attended a concert and spent the night with residing percussionist Billy Kreutzman roaming the streets after the concert banging on cars and walls and anything they could drum on.

Also, resident sound engineer Dan Healy enters the scene. When Hassinger finally quit, Healy and Garcia worked together to splice together the album from bits of live tape and whatever was salvageable from the early attempts to record in the studio. The logistics of the undertaking were often complicated, because they were splicing together multiple performances of the tracks for the album, each with different sonic signatures. The acoustics of any given venue could be varied, and the tempo and pitch might be different on any given night. The challenge was to create a seamless piece of music and coax the equipment to cooperate as they worked to record. To assist in the challenge, Garcia and Healy holed up in the studio with a nitrous oxide tank while smoking DMT, an incredibly potent hallucinogen.

Anthem was widely quoted as being “mixed for the hallucinations” by Jerry Garcia, but that certainly begs clarification. Was it the hallucinations the band experienced while mixing? Was it some attempt to create specific hallucinations for the listener? The ramifications there would be that the hallucination is less personal but more transpersonal. Whichever the case, a listen to the album can be a psychedelic journey as intended.

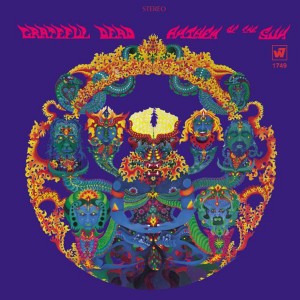

The cover design uses an old Tibetan image where the band members are featured as the faces of the multi-headed god. This particular figure was known in the Haight and was used as a mark to let people know that Deadheads (not yet the name for fans of the band) resided within and other heads were welcome.

The band wanted to learn the studio, and Anthem provided such a playground, perhaps to the dismay of their label. As Anthem was in production, the band was beginning to get pressure from the label, and their response was typical of their attitude toward the idea of authority. Warner Brothers President Joe Smith wrote a seething letter to the band intended to spurn the band to get their act together that was reportedly hung at the Dead’s offices, then still at 710 Ashbury, that said in response simply ‘Fuck You.’

The record, it seems, was not produced for the radio, and by extension it was not going to sell through as a billboard success. However, it is listed in Rolling Stone Magazine’s list of the best 500 albums of all time, at number 287. This is a testament to the place the Grateful Dead have taken in American music, as well as the industry’s ultimate acknowledgement of the unique production methods the Dead engaged in.

Anthem was described as a metaphorical acid trip, with chaos and confusion returning to order, and the first side rather embodies this. The first track, spanning over eighteen minutes, is divided into four titled sections, most reasonably for publishing and royalty purposes, and the sections were named more arbitrarily and with humor than anything else. “Cryptical Envelopment,” “Quadlibet for Tender Feet,” “The Faster We Go the Rounder We Get,” and “We Leave the Castle” all comprise “That’s It for the Other One.” Interestingly, a quodlibet is defined in the Oxford Companion as a “collection of different tunes or fragments brought together as a joke.” It was a device introduced by J.S. Bach in the Goldberg Variations, but is a rather classic example of the band’s sense of humor and how they would approach convention.

Garcia’s “Cryptical Envelopment” begins in slow, lamentable fashion, and arrives at the doorstep of rhythm guitarist Bob Weir’s “Quadlibet for Tender Feet,” which has a signature of 10/11 beats, cycling in what could be considered ordered chaos. “Cryptical Envelopment” was described as Garcia’s attempt to wrestle with the symbology of the traditional “Man of Constant Sorrow,” or the Christ symbology. Basically there is a man suffering here on earth and he goes to another place. In “Cryptical” the persecution aspect is clear, as well as the witnesses:

All the children learnin’ from books that they were burnin’

Every leaf was turnin’ to watch him die, you know he had to die

The song itself is a brief interlude, with the resolve of the necessity of this person, unknown and uncharacterized, to meet his death. There is no one to save him. The “every leaf” offers double entendre. Nature itself is an observer.

The work on Anthem offers a piece of music rather than a series of songs. It’s that interest in the performance of a long piece of music where songs are part of the structure, but parts of a greater whole—that the subject of suffering and death, both of the individual and of the symbol of man through Christ—embodying the entire mystery of life, death and meaning or religion. That it is wrapped around this incredible circle of rhythm is the richness and wealth of the Grateful Dead, how they operate, and what they were tuned into and what they were saying.

The “Quadlibet” portion becomes a rocket blasting off from the pensive and cryptic departure of Garcia’s song. The death transports us to some other vision or image, the ‘Spanish lady who lays on’ the singer this rose, and from there he is transformed in a spiral where he begins his journey to never-ever land. If a direct reference to the place in Peter Pan where no one grows up, this is a typical place to go, as far as the Dead are concerned. There is a childlike aspect to the spirit of the Dead that, for good or ill, is where one can travel or live. The song is an anthem to the time and place where the Grateful Dead reign. Cowboy Neal drives the bus to never-ever land, a direct reference to Neal Cassady and the bus in Kesey’s prankster world—a symbol of the new American adventure.

If the Dead’s body of work could be compared to a universe or solar system, the “Other One” would be a planet or star—with mass and energy, gravitational pull. During the initial development of material for this album, the band had two songs they were working on. One was “Alligator,” and the other, yet unnamed, was referred to as the “other one.” Another meaning would take shape as Mickey Hart joined the group as second percussionist.

The addition to the percussion personnel provided freedom to move beyond regimented beats, so standard 4/4 tempo that drives rock ‘n roll could be expanded with the additional drummer. The band could employ six beats under four or endless rhythm variations of time and pulse. Kreutzman and Hart could create these tempos and build in energy. The “Other One” was a demonstration of this metronomic freedom. It became a chase, or a thunder of drums keeping strange or varied numbers of beat in time, where they would often lose track of the first beat in the measure, or the “one.” Often one drummer would declare a new “one” and the band would follow, often one or two at a time, but when everyone got on the new “one,” they were able to swing and groove, feeling the “other one”—either emphasizing it or ignoring it entirely. The freedom to hold a tempo, even when another “one” is declared by one drummer, and the space to play around the “one” would really characterize the music of the Dead as they would carve out musical space or rhythms and syncopation. So, the “Other One” essentially came about musically in this fashion.

While the lyrics would come to Weir in phases, the song would become a psychedelic anthem and an anthem of sorts for the band as a product of the times. With lyrics cryptic and implying psychedelic experiences, and with personal references as well as the spiritual concept of the circle itself—a symbol of wholeness, of something closed and complete, without origin or end, of a cycle of infinite repetitive potential, which is reflected both in the lyrics and the driving cycles of the rhythm, driven by the percussive duo, the biting and cascading of Garcia’s dexterous fretboard work, Phil Lesh’s potent bass—the “Other One” operates as a vehicle for taking the trip through the cosmic. The development of the song is also a good testament to how the band worked. Early performances contained verses that would ultimately be discarded entirely, and their material was not perfected prior to taking it to an audience. Rather, it was always a work in progress.

Weir’s second verse would come together in February 1968 in Oregon, where a vision of Neal Cassady would appear to Weir—ironically on the night of his death. This is music that becomes anthem for a generation and memorial, circumscribing an experience and growing outward, affecting generations to come. This isn’t so much a reflection of the Dead’s deliberation and intent, but more their embrace of phenomenon. The bus became a symbol of the times, and its invocation in the “Other One” will forever bind it to that adventure. The idea is reflected again as it is in “Golden Road (to Unlimited Devotion),” where the invitation is open to any who are driven to that adventure. Grateful Dead fans would use the reference to getting “on the bus” to refer to the time that they began to follow the band.

Anthem is also a document of musicians beginning to compose. Phil Lesh wrote “New Potato Caboose” with his friend Robert Peterson, who would contribute three songs with Phil to the Grateful Dead. For their first effort together, “New Potato Caboose” begins quietly, and grows in intensity over a span of about eight minutes, and leads right to the first blasts of Weir’s “Born Cross-Eyed.” With some interesting melodic lines and rhythmic movements, “New Potato Caboose” is an eerie musical landscape that showcases both the psychedelic sound and sensibility of the Dead, as well as the stylings of Garcia’s guitar playing. The poetry is alarming, which is fused with the strangeness of the musical arrangements. While the landscape is haunting and barren, so is it also the place where “the seed of love is sown,” and “all graceful instruments are known.”

“Born Cross-Eyed” is a song partly about being inspired by the visitation of a song, and also expresses that romantic ideal of visiting such a place of inspiration again, in the “sweet bye and bye.” It may also be semi-autobiographical in that Weir struggled in school with dyslexia, so the title of the song may be a reference to that. It is rendered, like “New Potato Caboose,” with building intensity and weirdness that is part psychedelic, part rock ‘n roll, part musical eclecticism. Lesh plays a trumpet line after the high range melodic flourishes that adds a flavor of Spanish to color the arrangement, for example. Many of these kinds of accents throughout the album were added in the studio, which shows the Dead were using the technology to compose and arrange to embellish their live performances while still honoring the fact that they identified so strongly with being a live act. Likely because of the length of “Born Cross-Eyed,” another mix of the track would become the only single released in companion with the album, with the yet unreleased “Dark Star” as the B-side.

The second side of the album consists of a twenty-one minute “Alligator” and “Caution (Do Not Stop on Track),” which is still shortened in comparison to the live performances, is an extended jam that really showcases Pigpen and his persona as a devilish Don Juan blues singer. “Alligator” is Garcia’s old friend Robert Hunter’s first lyrical offering to the band, but hardly reflects his depth as a lyricist. It is a simple and playful song, beginning with kazoos, and taking on the form of hard electric blues riffing, again driven by Garcia’s electric blues guitar that seems to mirror the kazoos in the beginning. A percussion interlude creates a swampy rock ‘n roll ambience for a refrain from the group and the increased frenzy of Garcia’s playing that would reflect the kind of grooves that only came forth in performances because the band was developing their music on stage in the cooperative atmosphere they fostered for themselves. “Alligator,” like “Caution” was a vehicle for the kinds of expansive experimentation that the Dead were doing in their performances, and the second side of Anthem is an attempt to convey this.

“Caution (Do Not Stop on Track)” was so named because the band was playing frequently at a dive bar just in front of some railroad tracks. The percussion mirrors a freight train rolling past as it may have sounded to the band during gigs. Pigpen really steps into his role, bringing impish deviousness, raw sexuality and adventure to his own improvised lyrics.

The Dead used Anthem as an opportunity to learn how a studio works, but in their own unique style, used it to work for them in the way they discovered it could, and they did so with considerable efficacy. It is a very innovative creation, and it is really seamless in its production. While many of the live performances are identifiable, it is almost impossible to discern where the layers and cuts entwine. The innovation of the album is in its composition as sonic collage. While David Hassinger gets credit for producing, this is really an album produced by the Grateful Dead, which establishes a trend and a philosophy for them. To be in charge of their creation and to control its direction was a value important to them, and Anthem begins to establish this for them. The album was critically well received at the time, and that acclaim has stood the test of time. As for commercial success, the album did not fare as well; reaching a peak position of 87 on the popular music charts, and still is not certified gold by the RIAA.