Aoxomoxoa

Aoxomoxoa marks the completion of the band’s contractual obligation to Warner Brothers, and it is also is an interesting transition for the band’s musical development. Having developed into a heavily improvisational, free flowing jam band in live performances characterized by lengthy excursions, Aoxomoxoa, the meaningless palindrome coined by the album’s cover artist Rick Griffin, is a shift in both lyrical and musical structure. The band temporarily abandons long psychedelic jams in favor of shorter songs and structured lyrics that do more storytelling than inspire free-floating psychedelic exploration. One could argue that the new slew of songs that begin to tell these stories are part of the acquisition of balance and diversity to the repertoire as well as the development of the band’s sound and musical direction. While the songs may begin to offer more punctuation and decreased length, much of the material would prove to be the playing grounds for decades of musical exploration.

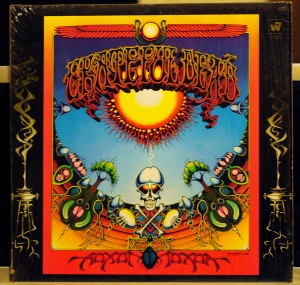

The album is rich in message, both musically and visually. Rolling Stone lists it as the eighth greatest album cover of all time, which is a considerable contribution to the annals of rock music and art. Griffin’s art is the penultimate in psychedelic imagery, where visual exploration reveals forms and images, as a mirror of the psychedelic experience. The title itself is hidden in the rendering of the scarab on the bottom, while the famous ambigram in the band name reveals the message, “We ate the acid.” The cover is replete with visual puzzles, and within that is the rich symbolism that Griffin depicts in such a striking visual manner. The interplay of opposites, of earth and sun, of birth and death—all are on display in his colorful and brilliantly imaginative artwork. The mythology of the Dead is again toyed with, as with the Egyptian imagery of the winged sun disc of Ra above their name. The cover flagrantly and boldly confronts the idea of death, and offers the entire cycle of birth and death as a visual whole. The phallus that inseminates the sun, burning with the tails of a circle of sperm, is rendered as a skull, whose skeletal fingers grip egg-like orbs as vessels of life, and its bones trail into the scarab beetle—a symbol of the self-contained scatological cycle of nourishment and waste, whose legs comprise the center of the album title. The trees and flowers hold life in their earth-bound wombs as life is conceived in the sun above. The entire image is seemingly composed around the image of an eyeball, an object that Griffin was particularly obsessed with, with the ovum-like sun as pupil. A visual explanation is perhaps an offensive thing to do to Griffin’s work, for it can speak for itself. But the ideas at play here are important. They speak to an ideology, a spiritual insight, the revelation of secret knowledge, and in a sense the palindromes and the ambigram reflect the piecing together of a puzzle or a mystery. That is part of what psychedelic art is, and the Grateful Dead are a seminal part of that movement.

While the cover art is rich in meaning, so too is the music within. Robert Hunter emerges on Aoxomoxoa as an exceptional poet and thinker, and essentially finds his own position as resident lyricist in collaboration with Garcia mainly, and it is the beginning of a prolific and rich partnership that would bare musical fruit for the better part of three decades. All eight tracks on the album are Hunter/Garcia songs, and they begin to show that his lyrics draw from the history of poetry and literature, and the vastness of the human experience. Themes and ideas, symbols and imagery are woven through all his songs, so that there are always relationships between them as well as the impact of the individual lyric. While not deliberately a concept album, there is a song cycle in Aoxomoxoa, as are there motifs throughout the entire body of the Grateful Dead’s work.

Having gained experience with recording in the studio, in an effort to retain hands-on control of the process as well as to find a way to use the studio’s technological capabilities to express themselves in a trial-by-fire type of approach, the Dead set out to apply this knowledge to produce a true studio creation. Aoxomoxoa is such an effort. Recording began in September 1968 at Pacific Recording Studios. They began with “St. Stephen,” and once they discovered the Ampex prototype, decided to start over using the 16-track device. In-house sound engineer Bob Matthews would acquire the machine, and he would work as chief engineer on the album, so the band was not reliant on the label’s engineering staff, and after the separation from Hassinger, the band would self-produce several albums.

By this time in 1968 the band’s repertoire had been pared down to 38 songs. That they sought to record new material for Aoxomoxoa is testament to their drive for creativity and growth—pushing themselves to explore new territory with the bountiful offerings Hunter was coming up with. Two songs would be submitted by mail, and then later Hunter would live with Garcia in Larkspur for the express purpose of songwriting. “St. Stephen” and “Chincat Sunflower” were sent in the mail.

Lyrically, “St. Stephen” is enigmatic, full of aphorism and truism and yet simultaneously, offers questions for contemplation. Certain leitmotifs run through the Dead’s catalog, and the rose is certainly one of these objects of meaning—it is St. Stephen that goes between worlds, or “in and out of the garden” with this rose. Hunter says of it that “the rose is the most prominent image in the human brain, as to delicacy, beauty, short-livedness, thorniness. It’s a whole. There is no better allegory for, dare I say it, life, than roses.” It is significant that Hunter draws from Judeo-Christian mythology, because it is embedded in our culture, and history, and is a manner in which we attempt to seek meaning and to answer the larger questions. In his music, Hunter will draw from numerous sources in history and literature in an effort to unify the human experience with common reference points, and to offer a landscape upon which to explore the meaning and experience of life. Extraordinarily, he uses stories and images and symbols that are part of the human experience from the beginning of time, or at least the beginning of language. They are parts of stories that we all know, or can learn, but they are part of our history. They are part of our collective attempt to make sense of the world, and the position we are in as human beings. And he gives them to us in song as a way to teach, to inform, and to cause contemplation, review, or generally inspire the psychic and heartfelt work of inquiry, in seeking the meaning and magic of life.

The analysis and deconstruction of poetry and song is a tightrope walk. My experience with this material is that the entire product—the words, the music and the way it is ultimately interpreted through musician and to audience through the years, all congeal into this living organic thing that is flexible and growing. It is no longer merely poetry when music is married to it. It is not so much simple song after the tribes dance to it. It becomes an entity that continues to grow. Yet, the richness of the tales being told, the symbols and images used to convey the sentiment, in many ways, begs for the inquiry that analysis can yield in terms of further illumination. Hunter was often pressed to divulge his meaning and intent, and often his response was to proclaim the inadequacy of such queries. Much of the difficulty to explain stems from the depth of the experience that he often writes about. These defy rationality and encourage or more require an open and flexible perspective. In a 1978 Relix Magazine interview, he is asked about the origin of St. Stephen:

Relix: Have any mystical experiences? Close encounters?

Hunter: I had a vision in San Christobel where I was offending the Indian Spirits somehow or another. I challenged them. My friend Karl Moore told me, “You ought to lay off that stuff; that stuff is real.” I said, “Well, I believe that I’m stronger than it is” and I hollered out a challenge. I was playing my guitar and challenging away, saying, “I’m heavier than any pack of ghosts” and, all of a sudden, I had a vision of a plain with slaughtered Indians all over it. They were slaughtered by the white man. That was all I needed and I gave a profound apology for it. I mean, they didn’t have to say any more.

Relix: There are reflections of that kind of thing in “Gommorah”. There’s something high above, but other than that, the song is totally open-ended. I’m sure you hear things from time to time in what you’ve written that you didn’t at all expect to convey. I imagine that Garcia might be less concerned than you are about meanings and would take more out and leave more to the imagination. Let you decide what it all means.

Hunter: What does it all mean? Boy, those Dead songs, the ones that are good, change their meanings from year to year and they seem to continue to speak to our condition. When we redid Saint Stephen a couple of years ago, after not doing it for years and years, it seemed to be a whole new song and to comment on the present situation. They continue to do that. Even in “The Eleven”—Now is the test of the boomerang, tossed in the night of redeeming.

Relix: Was Saint Stephen anyone specific?

Hunter: No, it was just Saint Stephen.

Relix: You weren’t writing about someone, you were writing about something?

Hunter: Yeah, yeah. That was a great song to write. I think it took a couple of nights of writing on that, of intense light feeling. It was like I was on to something there. I felt the radiance happening. I’d like to have some of those feelings again, some of those times when the light seems to be in your hands. You follow it along and some beautiful things just come to you.

A salient point here is that the song references the first Christian martyr, but that is essentially the point of departure for a broad sketch. The character and tale of St. Stephen is a doorway to allegory and a mirror for the self. Stephen was stoned to death for his speaking out against Judeo-Christian schisms and hypocrisy. As he orates for the last time up until the moment of his death about the covenant, the light of God shines on him, all the while his persecutors took no notice or were metaphorically blind. Hunter brings forth the character and perhaps cloaks him in contemporary robes, for he is perhaps a good comparison of the hippie ethos of the time, and the tale a reflection of how society responded. While Stephen goes in and out of the garden with his rose, “wherever he goes the people all complain.” Stephen is also used to challenge the notion of prosperity and the cultural values that the hip movement sought to challenge.

Stephen prosper in his time

Well he may and he may decline

Did it matter? Does it now?

Stephen would answer if he only knew how.

This view is expanded upon in the next verse:

Wishing well with the golden bell

Bucket hanging clear to Hell

Hell halfway ‘twixt now and then

Stephen fill it up and lower down and lower down again

The wishing well is juxtaposed against, or rather likened ironically to the idea of Hell, and yet the locale of Hell here is not a place so much as it is a time. The bucket he fills and lowers down perhaps reflects the manner in which he held hope for humanity, even unto his death, where in Acts 7:60 he asks God not to “hold this sin against them.” While time and space are distorted, so too is the syllabic count of the quatrain, where the second iteration of “lower down” disturbs the eleven syllables of the last lines of the previous quatrains. This aurally creates the sense of the descent.

All the richness of Hunter’s poetry is married to the musical composition in very interesting ways. The melodic themes that begin the song and return in variation throughout the song are Elizabethan, gothic, or perhaps medieval in nature, while the arrangement moves into rock ‘n roll so seamlessly, it defines the genre itself. The bridge is a shift from the sketches of Hell to feminine energy and light, and the variation on the melodic theme from the beginning reflects that sentiment, a transportation of sorts:

Lady finger dipped in moonlight

Writing ‘what for?’ across the morning sky

Sunlight splatters dawn with answers

Darkness shrugs and bids the day goodbye

It is this interlude, slow and deliberate, that brings forth the feminine influence, the hand that paints the morning sky with mystery, and dawn arrives under this wonderful melody coupled with these visually beautiful words and images. While the feminine serves to inspire a sense of wonder, the answers are not specifically provided beyond the fact that the dawn brings answers while darkness shrugs.

The next stanza in the bridge gives slight return to the conflict, still loaded with ambiguity.

Speeding arrow, sharp and narrow

What a lot of fleeting matters you have spurned

Several seasons with their treasons

Wrap the babe in scarlet covers call it your own

The ‘speeding arrow, sharp and narrow’ are perhaps a reference to the 91st Psalm, the arrow that flies by day, which has just brought answers but with it danger. Or perhaps they are a reference to the manner in which many martyrs were put to death. Whatever the specific turmoil, from within or without, with the appearance of this feminine energy brings forth a birth, or an opportunity to begin again, to leave behind the seasons of turmoil, of treasons and betrayal. The infant is born. It is something to parent, to ‘call your own.’

The bridge leads to the hard driving rock melody derived from the melodic themes in the beginning of the song, and the verse returns to the interrogatory, referencing the dilemma of St. Stephen:

Did he doubt or did he try?

Answers aplenty in the bye and bye

Talk about your plenty, talk about your ills

One man gathers what another man spills.

Running through the song is the interplay of questioning and finding answers. Stephen’s inability to answer questions about his rise and fall, or perhaps our inability to hear him as he walks between worlds; the broad ‘why’ that is written in the sky and the dawn that brings answers with its light; and here in this quatrain is the question of faith and action where answers are bountiful in the ‘bye and bye’—all are part of the wonder that the song inspires. The answers are illusive, but they are waiting. The notion of wondering, of inquiry and the quest for illumination is part of the emotional thrust of the song, but it seems to be set on the stage of life as a dance between opposing ideas and forces. The verse returns to the idea of the dance in life between having plenty and having misfortune, but it is also resolved with the idea that what is valuable to one is not to another, suggesting that such conflict is a matter of perspective. Replete with contraposition, the song reflects the dance between the opposites, between life and death, prosperity and want, masculine and feminine, inquiry and elucidation, darkness and light.

While all these questions abound in this dance of dualism, the next verse brings some resolve both musically, with the driving musical theme, and lyrically, with the assertion of St. Stephen’s locale:

Saint Stephen will remain

All he’s lost he shall regain

Seashore washed by the suds and the foam

Been here so long he’s got to callin’ it home

The idea of salvation and resurrection are clear. The conflicts, or the interaction of opposing ideas and forces, are reconciled here. He has regained everything he’s lost and will remain, purged like the seashore by the feminine ocean and in his home, born of his longtime presence there, as if without intent but as a mere matter of fact. The phenomenon described in this verse is not necessarily specific to Stephen, but open to all, and infers that it can be a personal and individual journey:

Fortune comes a crawlin’, Calliope woman

Spinning that curious sense of your own

Can you answer? Yes I can.

But what would be the answer to the answer man?

Again the idea of fortune is brought forth, juxtaposed against all the images of negativity in the song, by the feminine. Fortune crawls, reminiscent of the baby in the bridge, in the form of a Calliope woman. Calliope refers to the mother of music in the Greek pantheon, and inspiration in music and poetry in the deified personification of such inspiration. Here, that inspiration serves to assist in the forming of the individual, to aid the hero on his path of becoming. It seems as though the transformed hero, offers the resolve of the problem of all the questions posed throughout the song, because he can assert that he can answer, and yet the song ends with another question about answers. Such is the nature of life, and yet within the journey there is plenty to discover. It is for us to be inspired, to hold the infant in our arms.

As Aoxomoxoa marks a shift in the Dead’s music from long improvisation to the incarnation of more structured songs of shorter length, it also explores the song as a storytelling medium, as well as the continued spirit of exploring the American myth or folk tale tradition. “Dupree’s Diamond Blues” is a song that references the old tale of Frank Du Pre, the true tale of a man who was hanged for murder in 1922. The story was told in several blues songs of the era, most commonly known as the story of Betty and Du Pre. Frank Du Pre’s life became a story about the loss of judgment and morality in the face of his obsession with his lover, Betty. It is a tale of love, not in the romantic sense, but more of the consequential and real sense, musically arranged and delivered with a sense of humor. Hunter claims he wrote the song drunk, and admits it was the only song he ever wrote in such a state. While Dupree’s is a light hearted take on the tragic, it deals with the depth of common experiences, of love and what one is willing to do to secure romance and at what cost, the drive to love as the very cause of love lost and love thwarted. It is also framed as a lesson passed on from father to son. What is interesting about this song is the fact that it reaches into the collective and the traditional folk for inspiration, which of course pays homage to the past in a manner that declares the idea that lessons are not always learned from one generation to the next. The tale of the experience, ironically, is told time and again, from generation to generation and in varied musical traditions. The song pokes fun of life and the father-son relationship. The first verse is quite funny in that the father declares enigmatically that life itself isn’t very complicated, as there isn’t anything special to aspire to:

When I was just a little young boy

Papa said, “Son you’ll never get far

I’ll tell you the reason if you want to know

‘Cause child of mine, there isn’t really very far to go”

Musically it is humorous as well and in the acoustic arrangement we hear Tom Constanten’s organ sounding like a calliope, which creates this very interesting carnival or circus sound, while Garcia adds some banjo to the tune to create this atmosphere of fun and madness, which is tied quite well to Hunter’s tale.

Well you know son, you just can’t figure

First thing you know you gonna pull that trigger

And it’s no wonder your reason goes bad

Jelly roll will drive you stone mad

The admonition from father to his son tells that ‘jelly roll,’ an idiomatic reference to women, or women’s genitals, will cause madness and loss of reason. It is a perhaps a rite of passage to know this, and part of the wisdom passed from generation to generation. But for the irony of the entire composition, this so-called wisdom would be downright egregiously sexist. The judge who dispenses sentence to Dupree, for example, humorously offers his sympathy and confesses obtusely to his own tryst with Betty, while Dupree is quite accepting of his fate as he affirms the male rite of passage:

Judge said “Son I know your baby well

But that’s a secret I can’t ever tell”

Dupree said, “Judge, well it’s well understood

And you got to admit that sweet, sweet jelly’s so good”

The irony and tragedy work together to tell a story that is both humorous and timeless.

Aoxomoxoa also includes some technological innovation that reflects the collaborative nature of the entire Grateful Dead crew. Sound Engineer Dan Healy created a vocal phase shifter, then not known technology, to enhance the singing and to create a haunting effect that helps to create atmosphere on the tracks. One in particular, recorded on 4-track, features an acoustic guitar and the phase-shifted voice of Garcia to create a chilling, two-minute vignette called “Rosemary.” The song is like a weird breeze that blows in, leaving the listener’s mind with the wisp of memory, the wake of life and the mystery of decay. Rosemary, the herb of remembrance, was traditionally a funeral ceremony offering, left on the coffins of the deceased. Additionally, it was often a garland worn by the bride in wedding ceremonies so she would carry memories of her old life to her new one. In the song, Rosemary is a mysterious presence, sitting “quite alone” as a garden flourishes around her. Her presence in the garden rekindles the idea of St. Stephen’s passage in and out of the garden, and when she goes away, the flowers decay and the garden is sealed. The last couplet leaves its impression:

On the wall of the garden a legend did say,

“No one may come here, since no on may stay.”

It was originally thought by fans that Rosemary was never attempted live, but a single performance was unearthed, from Louisville, KY at Bellarmine College on December 7, 1968. Aoxomoxoa is a prized album for many reasons, but the document of material not performed makes it especially significant.

“Doin’ That Rag” is a song that never quite took hold in the live repertoire, and because only 31 live recordings exist, the document on Aoxomoxoa is particularly prized. Many songs would fall in and out of the repertoire in varied strength, but “Doin’ That Rag” was one number the band shelved, for one reason or another. One was the perceived inaccessibility of the lyrics for Garcia, who claims he couldn’t get comfortable with them. Thus, the version on Aoxomoxoa can offer a study in both the artists’ intentions and perhaps offer clues as to why the band felt it wasn’t something they could embrace in concert.

Whatever the case, “Doin’ that Rag” is a departure from the mysterious wisp of “Rosemary,” and an adventure into a different land.

Sitting in Mangrove Valley chasing lightbeams

Everything wanders from baby to z.

Baby, baby, pretty young on Tuesday

Old like a rum drinking demon at tea

The song is so stylistically Hunter, who weaves images and ideas that initially appear fantastic, outlandish, yet bear a closer look. He does not paint with words for color only. The verse suggests the course of a life, when everything is vibrant and beautiful and then aged and corrupted in the end. Interestingly, the youthful playfulness is at work here, and Hunter uses devices like the alphabet, an arguably childlike device, to reflect the process of learning in life, from baby to z. This album is not merely a series of eight songs, but a cycle of music that explores the cycle of life in all its depth and complexity.

Contrary to what some have posited, this song is not likely to be about ether! “That rag” likely refers to the style of dance born of the African American ragtime movement, a music characterized by syncopation and swing, which is paid homage to in the levity of the arrangement as well as the major and minor swing of the song itself. The early ragtime dance contests offered a cake as a prize to the winners, which of course is the origin of the term ‘cakewalk.’ It is rather that spirit the arrangement conveys about a certain time in life—of youth and innocence, while the minor intervals reflect a certain maturity and concern.

Despite the joviality of the arrangement, Hunter tends to remain caustic in nature, sometimes offering advice:

You needn’t gild the lily, offer jewels to the sunset

No one is watching or standing in your shoes

Wash your lonely feet in the river in the morning

Everything promised is delivered to you

The kind of advice Hunter offers leads perhaps to salvation and deliverance, as the image of washing off of feet in the river is very rife with the religious ideas of purging and cleansing, while the act itself leads to the fulfillment of a promise and deliverance, a typically biblical theme. The verse speaks to the idea of adornment and its moral or ethical implications, as with the needless gilding of the lily, and the dispossession of such adornment through cleansing. It is the water of the river that plays the role in such salvation. Water appears again in the second chorus, undoubtedly making a reference to the old African American gospel traditional, ‘Wade in the Water,’ but possibly with double and triple meanings:

Wade in the water you never get wet

If you keep on doin’ that rag

The gospel traditional is an anthem to the rite of baptism, the Christian cleansing of the soul, but it was also considered to be a secret, perhaps more subversive message to slaves attempting to make an escape to freedom in Harriet Tubman’s underground railroad, for a slave could throw off the scent of the dogs hunting them if they waded through water. The idea, too, is implied that if you do this dance, you will walk on water.

Another motif that would become common in Hunter’s work is the element of chance and fate, in the form of games and cards. The game certainly has the broader context of life itself, while the metaphors for fate and cards will be expanded upon in Hunter’s body of work. Here, ‘one-eyed jacks and the deuces are wild,’ and ‘aces are crawling up and down your sleeve,’ perhaps implying the wiles of the woman invoked at the beginning of the song. The singer wants to know the nature of these wiles, as well as the nature of the game of life itself, asking:

Is it all fall down?

Is it all go under?

The question is vague and yet far-reaching, using the spirit of nursery rhymes to inquire, invoking childhood as a way to capture the idea of wonder, the loss of innocence, and often the cold reality of death. Here, the question is about the nature of that reality, perhaps referring back to the water again and the idea of drowning. The question is not answered explicitly, but merely with the reiteration of the fact that everyone—‘hipsters, tripsters, real cool chicksters’—is doing that rag.

Aoxomoxoa paints a detailed portrait of the cycle of life, and it seeks to illuminate the passage. The loss of innocence and the idyllic time of childhood are but one aspect of the journey, but are certainly depicted in the Dead’s body of work. The tales and fables of childhood are themselves full of symbols and images that become a part of a person’s unconscious, and the symbols and themes still inform the adult, whether consciously or unconsciously. “Mountains of the Moon” is a song that does this.

“Mountains of the Moon” was recorded on 4-track, and as a result has an intimacy to it that helps strengthen its impact. Musically it creates an atmosphere of another time and place entirely, but with some concrete sense of its locale in the distant past. The harpsichord and acoustic arrangements create the feel of a king’s renaissance chamber, the Elizabethan court of music and dance, a minuet of courtship and caste. The atmosphere is captured in the first verse:

Cold mountain water, the jade merchant’s daughter

Mountains of the moon, Electra, bow and bend to me

Hi ho the carrion crow, fol de rol de riddle

Hi ho the carrion crow, bow and bend to me

The second couplet is stolen from Mother Goose, a nod to the experience of childhood as well as the poetry of the English nursery rhyme. In a single verse, Hunter paints with symbol and image, and includes enough ambiguity for the listener to have a personal attachment to the song, one that reaches into the collective, where earliest memories are planted. The carrion crow, feasting upon the flesh of the dead, is juxtaposed against the ‘fol de rol,’ in Mother Goose, and its impact is hard to define. Certainly it is a disturbing image from an adult perspective, yet through the eyes of a child perhaps less so. The juxtaposition between levity and seriousness is contained in the nursery rhyme, in the musical arrangement, and throughout Hunter’s lyrics as a dance balancing the two. Additionally, the mountains of the moon is an image open to interpretation, suggesting a dream-like fantasy land, or perhaps even a reference to the Ruwenzori Mountains in central Africa, which was explored as the source of the Nile River, perhaps metaphorically the source of life. Additionally the moon is again a symbol of the feminine, and the use of Electra infers the idea of the archetypal feminine drama and its resolution.

The minstrel-like character of Tom Banjo is thought to refer to Tom Azarian, a banjo player known to have traveled in the musical circles Hunter and Garcia would have at the time. In the song he is bestowed the hope of sowing ‘more than laurel,’ more than praise and recognition for achievement or victory in battle. In the second refrain, he is urged:

Hey Tom Banjo

It’s time to matter

The Earth will see you on through this time

The Earth will see you on through this time

While sowing more than laurel, he is told to matter, to fulfill his fate with the guidance of the earth, another feminine energy. The refrain continues, revealing Tom’s paucity:

Down by the water, the Marsh King’s Daughter

Did you know?

Clothed in tatters, always will be

Tom where did you go?

It is with that question that the song returns to the beginning, with the image of the mountains of the moon, Electra, the courtly dance, and the enigmatic nursery rhyme ending, and it does so with an order as ritualistic as the courtly dance the music imagines.

Interestingly, the Marsh King’s Daughter is a reference to another children’s fable of the same name by Hans Christian Andersen. The tale itself offers perspective on the song, and also continues to illuminate the themes that the entire album explores. Andersen mentions that this fable, handed down from parent to child, is a cousin to the tale of Moses, but is less known. A stork, the bird that personifies birth and parenting, tells the story. The stork sees a princess go on to the marsh, or mire, and falls down to the depth, where the Marsh King, who lives there, impregnates her. The stork witnesses a flower grow up from the marsh, and on its petals is a newborn baby girl. He takes the orphan girl back to his wife so she will care for her. As it turns out, a spell is cast upon the girl—by day she is beautiful, but mean and without mercy, while at night she turns into an ugly frog—but in that form she is delightful and happy. Her adopted mother struggles with the girl’s dual nature, and their relationship is akin to the Electra tragedy. The girl is transformed and healed when a Christian priest takes her, and she begins to have a conversion experience. A passage from the fable conveys the idea of salvation, deliverance and the hero’s journey (or in this case, the heroine) to effect such:

‘Thou daughter of the mire,’ said the Christian priest, ‘from the mire, from the earth thou art sprung; from earth thou shalt again arise. The fire within thee returns in personality to its source; the ray is not from the sun, but from God. No soul shall perish, but far distant is the time when life shall be merged in eternity. I come from the land of the dead; so shalt thou at some time travel through the deep valley to the shining hill-country, where grace and fullness dwell. I may not lead thee to Hadde for Christian baptism. First thou must burst the water-shield over the deep moorland, and draw up the living root that gave thee life and cradled thee. Thou must do thy work before the consecration may come to thee.

The priest and his horse die, but the girl resurrects them with the invocation of the “White Christ,” and he later returns home to the “land of the dead.” The girl loses her dual nature, completes her task, resolves her conflict with both her mothers, and marries an Arabian prince.

The tale, like so many of Hunter’s references, is invoked in the song to offer a thematic playground, a point of origin for context, while the song itself allows us to frolic in the storyland ourselves.

“Chinacat Sunflower” is another gem of poetry, where music and lyrics have the ability to transport and transform a listener. Certainly this is the by-product of the LSD experience, and Hunter’s muse was a cat sitting on his lap, who apparently took him to “all these cat places,” which is essentially the essence of the song. Consisting of three stanzas, it is a surreal portrait in words. Hunter was influenced by James Joyce, whose Ulysses and Finnegan’s Wake possess the similar stream of consciousness, and yet within the framework of the seemingly nonsensical lays meaning and order. It is as if the obvious transparency and perhaps limited explicitness or precision of language appears insufficient to express ideas beyond what language itself is designed to do, so breaking rules of syntax and structure can offer more for the efficacy of communicating concepts and ideas. Joyce could be said to have arrived at his implications and ideas by pure stream of consciousness, yet within that style is beheld his brilliance. “Chinacat Sunflower” unveils images, words that may have been born of the personal visions of its poet, but certainly the ritual repetition of the song for an audience begins to give it life and meaning of its own. Undoubtedly it is open to interpretation, but in the same token it retains some sense of its original intent and spirit. Hunter claimed that of all his songs, surprisingly, “Chinacat” was the one that nobody ever asked for explanations. It is as if the words themselves perform that on a level that typifies Grateful Dead music in general. It is to be experienced:

Look for a while at the chinacat sunflower,

Proud walking jingle in the midnight sun.

Copperdome Bodhi drip a silver

Kimono like a crazy quilt star-gown in a dream night wind

Here are images that simply are not meaningless strings of words—symbols and religious objects, such as the copper domed head of the Bodhi suggesting the enlightened end of the cycle of life and death described throughout the album—but visuals as signposts to ideas. His song is to be transformed from singer to listener, and often from lyricist to singer. Perhaps the images in “Chinacat” are intended to be dreamlike, surreal, as if to bring the listener to a dimension that isn’t like reality, but where the phenomenon of the poetry is offered up as a place where everything has depth and beauty uncommon and the mystery is part of the experience. It would suggest the psychedelic experience as one where perception is changed, and the orientation of what was normal is not anymore. It is a place where cats can take you on a journey of discovery.

Krazy Kat peeking through a lace bandana

Like a one-eyed Cheshire like a diamond eyed jack

A leaf of all colors plays a golden string fiddle to a

Double-e waterfall all over my back

Images unfold in a crowded dance, where George Herriman’s Krazy Kat conjures the image of Lewis Carrol’s Cheshire cat in a playful game, while this hallucinatory image of nature in its vibrant colors communes with the human form in a sacred musical interlude. Despite the many images to decipher, the impression is potent, for it is the imprint left behind of vision.

The playful meter and the spirit of the wordplay, Hunter explains, was the influence of the English poet Dame Edith Sitwell, which is easy to see in her poem entitled “Polka:”

While the wheezing hurdy-gurdy

Of the marine wind blows me

To the tune of Annie Roonie, sturdy

Over the sheafs of sea;

Hunter’s last line is stolen with two hands from Sitwell’s “Trio for Two Cats and a Trombone:”

Or the sound of the onycha

When the phoca has the pica

In the Palace of the Queen Chinee!

Musically, “Chinacat” reflects the rhythm of Hunter’s meter, with a shuffle and syncopation in Garcia’s guitar part. The arrangement of Aoxomoxoa varies from the live arrangement with the addition of vocal harmony and organ accents throughout, but the real driving force in both studio and live renditions is the steely razor of Garcia’s guitar, which somehow renders a cosmic feline spirit with precision, and catapults the listener into the dimension of Hunter’s vision.

As Garcia transports us musically, his interludes return to the surreal landscape of Hunter’s visionary poem, and yet in counterpoint to Garcia’s guitar voicing, when Garcia sings each verse it feels like terra firma:

Comic book colors on a violin river

crying Leonardo words from out a silk trombone

I rang a silent bell beneath a shower of pearls in the

eagle-winged palace of the queen Chinee.

The universe of “Chinacat” may be visionary and otherworldly, but it is a place we can understand in our imagination, and thus it is perhaps more accessible and comprehensible than we might assume. Music and color blend in an experience of synesthesia. The ‘Leonardo words’ perhaps refer to the mirrored writing in Da Vinci’s work, and by extension it is complimented by the ambigram and the palindrome of Griffin’s cover art—suggesting again the puzzling out of mystery, of symmetry, of looking-glass poetry in our own Wonderland, of the cycle of life. In places of dream-like majesty, we can see past the mundane and gain insight. The ‘silent bell’ can ring, showering us with the pearls of enlightenment.

“What’s Become of the Baby” is perhaps one of the stranger pieces of Grateful Dead output. It features the phase-shifted voice of Jerry Garcia singing in shifting keys a bizarre poem posing the question, “What’s become of the baby this cold December morning?” The origin of the question is possibly culled from Alice in Wonderland, where the Cheshire Cat asked Alice, “what became of the baby?” While this certainly makes sense in light of other references to Carrol’s work in the album, it is also a point of origin for further reflection on the same themes explored throughout the course of history—adulthood as the loss of innocence, the fragility of life, the cold reality of aging and death. Innocence and vulnerability is captured in the second verse:

Songbirds frozen in their flight

Drifting to the earth

Remnants of forgotten dreaming

Calling

Answer comes there none

Go to sleep you child

Dream of never ending always

Hunter refers to Carrol’s Wonderland as well as the opium-induced vision of Samuel Coleridge Taylor’s “Khubla Khan,” where the sacred river Alph leads to caverns ‘measureless to man,’ and the paradisiacal pleasure-dome resides.

Panes of crystal

Eyes sparkle like waterfalls

Lighting the polished ice caverns of Khan

But where in the looking-glass fields of illusion

Wandered the child who was as perfect as dawn?

Hunter’s literary references provide the context for his own expression, and his lyrics inspire inquiry into these. In Taylor’s poem, the ideas Hunter has played with throughout the album coincide thematically. Taylor’s ‘damsel with the dulcimer,’ who inspires the poet to perform the work of building his pleasure-dome, speaks to Hunter’s fascination with the female muse. But again, it is less Hunter’s fascination than it is the recurrence of similar themes throughout human history that is wondrous and inspiring, and Hunter references these to tell the story of humanity in all its depth and richness.

In comparison to Taylor’s utopian vision, “What’s Become of the Baby” is darker and more acerbic. However, the two works convene around the idea of divine insight and both are cautionary. Hunter’s fourth verse begins:

Racing rhythms of the sun

All the world revolves

Captured in the eye of Odin

Pray Allah where are you now?

All Mohammed’s men blinded by the sparkling water

Odin, the major god in Norse mythology, representing wisdom, war, magic and poetry, among other attributes, was also considered a guide of souls. Odin sacrificed his eye to the well of Mimir, a mythical well under the tree of Yggdrasil, whose three roots extended throughout the divine universe. The Norse myth calls to mind “Mountains of the Moon,” for Hans Christian Andersen’s Danish culture shared much with Norway’s. As an aside, Odin’s sacrifice was an Oedipal gouging, and expresses also the paradox of blindness and sight. This, juxtaposed with the references to Electra in “Mountains of the Moon,” offers a possible marriage between the two songs.

Mohammed, referenced here, was known to have turned his back on a blind man, perhaps reflecting the sentiment here in the call to Allah—a sense of abandonment, or bitter bewilderment about the nature of life and the desire to see the divine. Hunter traverses the map of myth and religion, but never strays from his own inquiry and expression:

Sheherazade gathering stories to tell

From primal gold fantasy petals that fall

But where is the child who played with the sun chimes

And chased the cloud sheep to the regions of rhyme?

Sheherazade was the storyteller of One Thousand and One Nights, or the collection of tales more commonly known as the Arabian Nights. Married to the Persian king who killed his wives to take a new, virgin wife every day, Sheherazade kept herself alive by telling the king stories in the hopes that his curiosity would ensure her another day of life. Here Hunter uses another muse-like character to characterize survival, while again calling out the original question. The question remains, and perhaps answered in the last verse:

Stranded cries the south wind

Lost in the regions of lead

Shackled by chains of illusion

Delusions of living and dead

While this track on Aoxomoxoa is haunting and nearly inaccessible as music, the Dead did attempt to render it live once on April 26, 1969 at the Electric Theatre in Chicago. Much like “Rosemary,” this track was created in the studio, not in live performance, making them a rare portion of the Dead’s body of work.

The final track on the album, “Cosmic Charlie,” is a loping blues arrangement. The song itself is more admonition than homage, where the Cosmic Charlie character is mocked and encouraged to go home to his mother because he is too wide-eyed. In juxtaposition to the idea of adulthood as a loss of innocence, those that fail to mature are deemed to be outcast or unwanted. It begins with mockery and rejection:

Cosmic Charlie how do you do?

Truckin’ in style along the avenue

Dumdeedumdee doodle-ee doo

Go on home your mama’s calling you

“Cosmic Charlie” appears to be a caricature common to the era, where young adults ‘turned on’ to LSD and built an identity or a persona out of the experience. Despite the tone of mockery, the song in a broader sense also deals with the strange and chaotic passage of time, as in youth and in adulthood, and ultimately that life passes quickly. While we are here, there is a strange and cosmic dance at work. Childhood clashes with adulthood, and Hunter conveys the depths of the emotion with images of childhood toys, urgency, energy, psychedelic vibrancy, humor and irony:

Calico Khalia come tell me the news

Calamity’s waiting for a way to get to her

Rosy red and electric blue

I bought you a paddle for your paper canoe

There is a sense of the casual, and the ease with which we can relate to one another as we go through life:

Say you’ll come back when you can

Whenever your airplane happens to land

Maybe I’ll be back here too

It all depends on what’s with you

Hunter combines whimsy and the casual with the wonder that we take with us into our respective futures. There is honest uncertainty about the future, about whether we will re-connect with people we know, and the acknowledgement of the interdependency of human relationships.

In “Cosmic Charlie,” it is established that we will journey in the circle of life, from the womb to the place of returning, but Hunter is concerned with what happens in-between, with how we live and how we appreciate what is happening to us. As a child, we do not consider the urgency of life, but merely the urgency of our desire to play:

Hung up waiting for a windy day

Kite on ice since the first of February

Mama Bee sayin’ that the wind might blow

But standing here I say I just don’t know

The experiences and emotions that Hunter paints in verse are similarly expressed in the musical arrangements. Here, whimsy, pensiveness, and wistfulness are rendered musically through the loping tempo, the wailing slide guitar, and the descending vocal harmonies that accent the bridge. It trucks along in style like Cosmic Charlie, or like the rhythm of this procession of life, which moves in a time all its own:

New ones coming as the old ones go

But everything’s moving here but much too slowly

Little bit quicker and we might have time

To say ‘how do you do’ before we’re left behind

As adults we begin to see life moving faster, and the smooth blues of “Cosmic Charlie” lopes along as a reflection of a lifespan, of the lament of our yearning to connect with each other, and of the reality of the passage of time.

The song, like most Hunter creations, are replete with ambiguity and cryptic lyrics, and to puzzle them out, on one hand, is to fairly well dull the sensual and psychic experience of song itself. A song becomes what it is intended when it moves the listener. Granted, one can be moved to decipher a songwriter’s references and allusions, his symbols and signs, or his foot and meter—but often ambiguity is part of the experience that makes a song stay in the listener’s heart. In “Cosmic Charlie,” there is a seemingly obvious reference to mortality—a simplistic structural view of life insofar as it consists of birth, life and death. But it is in the space between where “Cosmic Charlie” grooves.

Calliope wail like a seaside zoo

The very last lately inquired about you

It’s really very one or two

The first you wanted, the last I knew

The idea of denoting the ‘first’ and ‘last,’ as well as ‘one or two’ in this second bridge is perhaps the obvious reference to birth and death, but to do so is too reductive, nearly heretical. There remains an uncertainty, an ambiguity, despite the singer’s attempt to stress simplicity in the same familiarly cautionary and wise tone. In the parlance of “Cosmic Charlie,” the last verse is a return to the first verse, where the singer’s bemusement and concern offers some guidance in light of what came before:

I just wonder if you shouldn’t feel

Less concern about the deep unreal

The very first word is ‘how do you do?’

The last go home your mama’s calling you.

The ‘deep unreal’ is open for contemplation as to its intended meaning. Perhaps it is the illusory nature of the material world, or perhaps it is an ironic statement about the problem of too much thinking. It seems that despite the developments throughout the song, the basic situation is the same. It is the moving image of a character for contemplation that seems to truck in with a strut, and passes through as a breeze. It is for us to say, ‘how do you do?’

The Grateful Dead exist in part because of a cycle of folk tales from where their name is derived. It was not a name that anyone in the band really embraced, but rather was accepted reluctantly and often with trepidation. The naming of the band was a way to allow a phenomenon to take place, in a sense. It was a name that invoked all kinds of spirits, emotions and ideas. In their third album, the Grateful Dead marked another phase of becoming. Aoxomoxoa is a very honest, truthful and wholehearted effort to stand unabashed in front of the listening world, for the Grateful Dead to begin to explore who they are as a band, as human beings, as seekers.

Robert Hunter cements his spot as resident lyricist, and the material that he writes with Garcia continues to define the Grateful Dead. They continue to explore their own mythology, while exploring subject matter that matters to them. They dive headfirst into the human experience and the ways in which we attempt to explore our own reason for being. They rather appear as purveyors of the human myth, to express the sentiment and the richness of the experience of what it means to be alive, and how we are connected inexorably to our past through our history and art, through our literature, music and poetry. This is music that seeks to explore the vastness of the human experience, to share the revelation of vision and inspire others to share in kind. It is music that will naturally endure.